For most shapes, the dimension is pretty clear. A line is one dimensional — it has only length, no thickness or depth. A square is two dimensional — it takes up area, but not volume. A cube is three dimensional — a real one could be sitting on your desk.

But what about fractals?

The boundary of the Koch snowflake (partly shown above) should probably not be two dimensional since it’s just a line that’s been crinkled infinitely many times. But it also probably shouldn’t be considered one dimensional either — it’s been crinkled so many times, it’s infinite length and almost takes up area.

So, how many dimensions does it have?

Close, but you’ll spoil it!

First, let’s talk about dimension.

There are many ways to define dimension, from topological dimension to the Hausdorff dimension. Different definitions are useful for different fields of mathematics, but they all agree for simple shapes.

The simplest definition of dimension is the one we used when we were talking about manifolds back in Asteroids on a Donut. Basically, a line is one dimensional because you can only go in one (pair of) directions — left and right. A square is two dimensional because you can go left and right and up and down. And so on.

Unfortunately, that stops working so well when you start dealing with fractals. After all, which directions can you go on the Cantor set?

The Cantor is set is just a bunch of disconnected points. There isn’t a direction to go when you’re on them. But there’s a whole bunch of points (uncountably1 many, in fact), so maybe it doesn’t make sense to say it’s zero dimensional.

To make sense of things like the Cantor set and the Koch snowflake, we need a definition of dimension that’s a bit more robust.

To figure out how to define dimension, let’s look how size grows when we double lengths.

For a line, if we double the lengths, the line doubles in length.

In other words, doubling the lengths makes the line times as big.

For a square, if we double the lengths, the square quadruples in area. That’s because there are two directions for doubling to affect, so doubling the lengths makes the square times as big.

For a cube, if we double the lengths, the cube octuples in volume. For a cube, there are three directions for doubling to affect, so doubling the lengths makes the cube times as big.

See where I’m going?

One way to figure out a dimension is to make it bigger by multiplying each direction by two. Just like multiplying the lengths of a cube by 2 increased its size by a factor of , if we multiply the lengths of a

dimensional shape by 2, then the size of the shape will have to expand by a factor of

.

Multiplying by 2 isn’t special, of course. If we multiplied each length by a factor of 3, the size of a shape of dimension would have to expand by a factor of

.

Now, let’s take this new measuring stick and try to measure some fractals!

Even Benoit Mandelbrot, often considered the father of fractals, had trouble nailing down an exact definition for what a fractal is. But a good intuitive idea is that a fractal is a shape that looks roughly the same, no matter how much you zoom in.

For example, if you zoom in on a circle, it quickly stops looking round, and begins to look straight.

But, for a fractal, no matter how far you zoom in, it keeps on repeating itself.

While “most” fractals aren’t exactly self similar (for instance, the Mandelbrot set), many of the simplest examples are. To make one, start from a simple shape, then repeatedly change it in the same way, on smaller and smaller scales, infinitely many times.

For instance, the Koch snowflake.

To make the snowflake, start with a triangle, then, add a spike to each side. Then, for each of the new, smaller sides, add a new spike. The Koch snowflake is not any of the intermediate steps, but the limit of doing infinitely many steps.

So, what’s the dimension of the snowflake?

Remember, what we’re looking for is a scaling law — if we multiply each length by a factor of 3, the size of a shape of dimension would have to expand by a factor of

.

How does the snowflake scale?

Consider one side at a time. Each side becomes four sides, of one third the length.

If you take one of these little mini-sides, and triple the lengths in each direction, then each one of these mini-sides will become as big as the entire original side. For instance, the little spike on the left flat part expands to be the same size as the big spike in the middle of the original.

Since the original side was four copies of the mini-side, that means that if we triple the length in each direction, then we quadrupled the total size of the shape.

Using the pattern that a dimensional shape should get

times bigger, we have that

. Using a logarithm, we get that the dimension of the Koch snowflake is

. More than a length, a bit less than an area.

Let’s do another example of a fractal, this one somewhere between a point and a line — the Cantor set.

To make the Cantor set, you start with a line. Then you cut out the middle third. Then, from each remaining piece, you cut out it’s middle third, and so on, until you’re left with a fine dust.

To figure out the dimension of the Cantor set, look at the left segment after the first excision. Since we are just cutting out middle thirds, this little segment becomes an exact copy of the entire Cantor set, just at a smaller scale.

If we triple the lengths, then that small segment becomes the original Cantor set. But the original Cantor set is just two copies of that smaller piece. Thus, tripling lengths doubles size, so , and

. Not really a line, not really a point.

With any of these self similar fractals, you can do a similar trick, without too much problem. For instance, the Serpinski Carpet, which is made by taking a square and repeatedly cutting out the middle ninth, increases in size by a factor of 8 whenever the lengths are multiplied by 3, and so has a dimension of , so

.

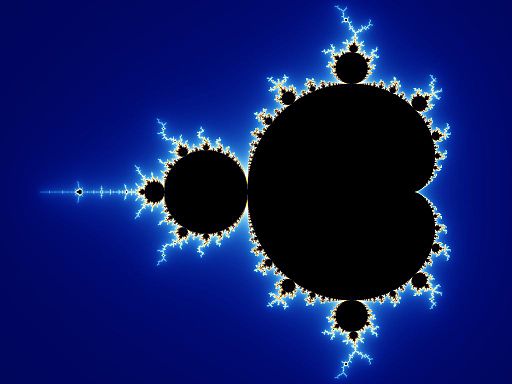

Many of the most awesome fractals aren’t exactly self similar, like the Mandelbrot set.

The Mandelbrot set is defined by looking at each complex number individually, then repeatedly calculating

. (For example, if

, then we make a sequence

,

,

, etc..) If this sequence becomes infinitely big, then the original

is not in the Mandelbrot set. If, like for

, this sequence stays close to zero, then that

is in the Mandelbrot set.

The Mandelbrot set is famous for it’s beauty, and for the nearly repeating, but infinitely varied patterns you find when you zoom in.2

Actually, from that definition, you might realize that only the black parts of the pictures are the Mandelbrot set. The pretty colors come from counting how long it takes for the sequence to get large enough to be sure it won’t stay small.

Well, the Mandelbrot set itself is, of course, 2-dimensional, since it has area. (It can’t be three dimensional since it’s already confined to a plane.) But what about its boundary?

It’s a really zig-zagging line, like the Koch snowflake, but it’s not exactly self-repeating, so we can’t do the same tricks we did before. Just from the previous examples, you probably expect the dimension to be somewhere between 1 and 2, which seems reasonable.

Mandelbrot himself conjectured that the boundary was so zig-zaggy, so fractal, that it would somehow skip pass crazy dimensions like , and go all the way to two dimensions.

This turns out to be true. Shishikura managed to prove in 1998 that the boundary of the Mandelbrot set is two-dimensional. The proof is a biiiit complicated, so we won’t go into it here, but it does work.

Normally, the boundary is one dimension lower than the main part of a shape. For instance, a square is two dimensional, but its boundary is one dimensional. Fractals can be a bit different. For instance, we had the Koch snowflake. The inside is two dimensional, but the boundary, as we said earlier, is dimensional. Still less than two.

The Mandelbrot set itself is also two-dimensional. But, somehow, the boundary is so jagged that it manages to have the same dimension as the set itself.

That’s… bizarre.

But that’s how fractals roll.

Sorry for taking so long on this post. I wrote an entire other post about waves, which took forever… but then I decided it wasn’t very good. Hopefully I’ll get a better angle on that topic eventually.

<– Previous Post: The most controversial axiom of all time

–> Next Post:

- Uncountable means infinite, but like super duper infinite. Countably infinite means you can line them up with the counting numbers 1, 2, 3… Uncountable is somehow a bigger kind of infinity. Way more than infinity plus one. Ahem. Anyway, if you’re curious how you can be bigger than infinity, go back to the very first post, Infinity plus one. ↩

- A Mandelbrot set generator isn’t that hard to make yourself, if you know how to program, or there are a number of generators available for free online, such as this one. ↩

Really nice explanation.

LikeLike

Very accurate and yet very simple. Congratulations!

LikeLike

Sounds to me that it’s just the wrong definition of dimention for the boundary of the Mandelbrot set.

LikeLike